by Graham Taylor.

Last January the Quaker Socialist Society (QSS) suffered a historic loss with the death of Grace Crookall-Greening. Grace had been a founder member of QSS in 1975, Convenor of QSS from 1976, and was still on the Committee in 2018. It was largely through her hard work, dedication, and quirky stubbornness that QSS flourished over five decades, and it was largely through her that the achievements of QSS – the Social Testimony, the Salter Lectures, the working co-operatives – were brought about. The QSS had been founded by the charismatic Ben Vincent – Classicist, Bible scholar, and a veteran of the old Socialist Quaker Society founded in 1898 – but by 1975 Ben was elderly, and it was Grace who did most of the work.

Grace Greening came from a working-class background. Her father was a cabinetmaker who worked for Co-operative Wholesale and he was also a Baptist lay preacher. At Baptist Sunday School she won certificates for memorising chapters in the Bible, and all seemed well. Unfortunately, a generous member of the congregation, impressed by her talent, paid for her to attend a private school, and she hated it. She played truant and cycled off into the Cheshire countryside to read ‘pagan’ (secular) books disapproved of by her father, the church and the school. From this act of juvenile rebellion she gained her life-long love of nature, as well as an encyclopaedic knowledge of trees, flowers and birds.

In 1943 she escaped the dreaded private school and entered a commercial college. She then further shocked her parents by becoming a junior reporter on the Manchester City News, instead of getting a ‘proper job’. She was a rebel by nature; she trusted implicitly in her own instincts; and she was stubborn as a mule.

Her future development seems to have been prefigured by these events of her youth. Her revulsion against private school prefigured her socialism; her father’s work prefigured her love of co-operatives; and trust in her own instincts prefigured her Quaker trust in following the Inner Light, regardless of whom it might offend.

In 1957 she married John Crookall, a scientist, at St Giles in the Fields, Holborn, an Anglican Church. After the disaster at the nuclear power plant now called Sellafield, John began studying radioactive fallout. His horror at the threat from nuclear radiation drew them to the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). Their participation in the Aldermaston marches organised by CND then led them to become pacifists and Quakers, and this led them to other peace campaigns, in particular for Vietnam. By 1972 Grace was supporting a daily vigil for Peace in Vietnam outside the American Embassy.

There remained the outstanding question of her self-disrupted education but, while living in Crawley, Surrey, now with two children, Olwen and Chris, Grace studied at Labour’s newly founded Open University. She was awarded a Social Science degree, followed by a Post-Graduate Certificate in Education (PGCE). According to Olwen, Grace’s daughter, she did teach for a while at a Catholic school and enjoyed it but then perhaps inevitable tensions emerged after she had a discussion with her class about birth control. Grace and schools did not seem to mix.

Everything was easier after she used her journalistic experience with the Manchester City News to get a Quaker job at Friends House, as Publications Officer. She became editor of Labour Action for Peace, and formed friendships with trade union leaders such as Quaker Ron Huzzard, with Labour MPs such as Tony Benn, and with Methodist preacher, Donald Soper – sitting for political reasons in the House of Lords, an institution he deplored.

It was from the Christian Socialist Movement (CSM) led by Soper that in 1975 the Quaker Socialist Society emerged. In the summer Ben Vincent had raised the idea of a Socialist Society and by November Grace was reporting in the Friend that the CSM had convened a meeting of Quakers “to form a new Quaker socialist group”. The Quaker Socialist Society formed that December was backed not only by Soper but by two Labour MPs, Guy Barnett and Fred Willey; by the trade unionist, Ron Huzzard; and also by the Quaker Nobel Prize-winner, Philip Noel-Baker. Grace was made ‘Convenor’ of the QSS, although Ben Vincent was clearly the leading light.

In 1977 Grace caused a minor storm in Quakers when a letter by her was published in The Times and signed “Grace CG, Convenor of the Quaker Socialist Society”. Posh Quakers, it seems from the response, were appalled that readers of The Times would think Quakers were connected in any way with ‘socialists’. Ben Vincent thought it was hilarious – Are the readers of The Times really imagining a lot of Red Quakers donning “red ties as they go off at six in the morning to their chocolate factories?”, he asked. Grace did fail to consult the QSS Committee, yes, but that was no great sin – “well, all right then, we’ll tick dear Grace off.”

Grace was characteristically unrepentant. She had acted from the best of intentions: “I’m sure my letter will have done the readers of The Times, and the Quaker Conservatives, a power of good.” Her son, Chris, said at her memorial service earlier this year that her “magnificent stubbornness” was “always unrepentant”. She would never take instruction from anybody – not even from recipes in a cookery book. Some of her meals were “shocking”.

Grace pursued a different agenda from Ben and maybe a different agenda from the rest of QSS. In 1973 she had been inspired by reading a new book, Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered by E.F. Schumacher, which objected to mega-companies and mega-capitalism destroying nature and destroying working-class communities. This environmentalism fitted in with her love of nature and with the QSS idea that the ‘socialism’ they stood for was not one dominated by the state but one such as Keir Hardie wanted: a countrywide network of co-operatives. Impressed by the Bader family in Northamptonshire, who had handed over their chemical factory to their employees to be run as a co-op, she joined the Scott Bader Industrial Common Ownership Movement (ICOM) and was even made a director. It was quite a success, and led to the formation of hundreds of small or medium-sized co-operative businesses across the country.

Inside Quakers Grace’s major achievement was to bring about, with Jonathan Dale, the formal recognition of a Quaker ‘Social Testimony’. George Fox, who founded Quakerism in the 17th century, had pursued equality from the start of the Quaker movement, and peace was added only later. Grace believed it was necessary to restore that original emphasis and make equality as important as peace. She thought it was from the inequality between regions and countries that war derived.

In 1982, at Yearly Meeting in Warwick, Grace delivered the QSS lecture that is now known as the Salter Lecture. Her title was Capitalism – A Cause of Social Unrest, Injustice and Fear. In this she argued that Christianity and capitalism were incompatible and the ‘ethical socialism’ of QSS was the modern political expression of early Quaker beliefs. Capitalism was so destructive it would destroy itself, or the world, and the socialism that would replace capitalism had to be a network of co-operatives, run by workers and managers along the lines of Scott Bader. A minute was sent to the Clerk of YM asking British Quakers to adopt a Social Testimony based on the Quaker ethical value of equality.

Jonathan Dale wrote after hearing of Grace’s death: “Grace had a burning conviction that we needed to create a new Social Testimony, to build on the 1918 Eight Foundations of a True Social Order. Her steadfast commitment to this vision certainly fed into my work as Clerk of Quaker Social Responsibility and Education… Between 1990 and 2005 I think we can say that Grace’s vision of a transformed British Quaker movement was achieved.”

To Grace’s astonishment her lecture created not only discussion within British Quakers but evoked an international response, in particular from New York and Moscow. In New York Quaker Socialists had long wanted to found a QSS but it was not possible in America to use the word ‘Socialist’ without provoking immediate hostility. Now, seizing on Grace’s idea of an ethical socialism based on Bader’s worker co-operatives, they invited Grace to New York to deliver her famous lecture over there. Grace flew to New York in June 1983. After hearing Grace, New York Quakers founded the Quaker Society for Economic Democracy (QSED), the first branch of QSS in America. The QSS paid her expenses for the trip: £810 (7 nights in New York plus the flight).

In Russia the problem was the exact opposite to that in America: the word ‘socialism’ was accepted but anything religious was regarded with suspicion. Russian Quakers had long been struggling to find common ground with Soviet socialism but lacked the right words. For them Grace’s lecture, published as a pamphlet, was a life-line. Her lecture was also greeted enthusiastically in the GDR (East Germany) but that was easier. In the GDR the Quakers, highly regarded for their relief work in 1919 and for the Kindertransport, had always been treated with respect.

Grace’s lecture may not have made any impact on Russia except that in 1985 Gorbachev came to power and started to liberalise Russian politics. Grace was working in the Peace Department of Friends House, as Assistant Peace Secretary to Ron Huzzard, and she discussed with Eleanor Barden, who was on the Peace Committee, the idea of sending Quaker tourist groups to Russia. In July 1986 Grace and Eleanor flew to Moscow with Quaker diplomat William Barton (fluent in Russian and with contacts in Moscow at the highest level). She explained worker co-operatives to the Russian Communists, and they listened politely. This cleared the ground for Quaker tourism across the ‘Iron Curtain’ and in 1986 she and Eleanor launched a company, advertised as ‘Meet the Russians: Goodwill Holidays in the Soviet Union’. As usual with Grace, there were no half-measures. By the end of 1986 she had set up a dozen ‘Meet the Russians’ tours for 1987.

On one trip Grace met Tatiana Pavlova, a Russian historian who had written about John Bellers, a 17th century Quaker identified by Grace (and by Marx) as a pioneer of Quaker Socialism. Tatiana was enthused by Grace’s Quaker Socialist initiative, and later set up a Moscow Quaker Centre, which is still active to this day.

In 1997, though a Labour government led by Tony Blair was elected, it was not as radical as Grace wanted and in 1998 she resigned as ‘Convenor’ of the QSS. To be clear: only she called the role ‘Convenor’, and not ‘Clerk’. QSS had been founded in 1975 to take the Quaker message out to trade unionists and peace campaigners. They understood what a ‘Convenor’ was, but not a ‘Clerk’. It therefore made no sense to say ‘Clerk’ if that would defeat the objective of QSS, so Grace would not say it. Following her resignation she was replaced almost overnight by Barbara Forbes not only to general surprise but to Barbara’s surprise. Barbara later explained: “What actually happened was that Grace sent round a notice to everybody saying that I had agreed to take over from her as ‘Convenor’ – except that she hadn’t actually asked me!” Everyone smiled – this was ‘typical Grace’.

Grace used her extra time to combat the Conservative Quakers who opposed the Social Testimony. She unleashed a strong attack on the 2001 Swarthmore Lecture, delivered by the leading light of the Conservative faction, Tony Stoller. She was also refining her own position. At her final AGM the speaker had been Labour MP, Clare Short, and in her AGM report Grace quoted Clare’s words: “When people talk about the death of socialism they mean either the end of communism or the end of Keynesian economics. But socialism is an ethic which recognises the full value of every human being.” This was Grace’s Quaker Socialism. This was what Grace herself believed.

After her husband, John, died in 2009, Grace produced a late flurry of Quaker Socialist writings, promulgating her ethical socialism. In 2011 she co-authored Labouring for Peace with Rosalie Huzzard – a history of Labour Action for Peace, and its long struggle for peace policies inside the Labour Party. She wrote a dozen essays and booklets in a few years: on Bader and worker co-operatives; on the 17th century Quaker, John Bellers, praised by Marx and Owen; and on radical Quaker economics, derived from Schumacher but updated by John’s scientific concern for climate change.

In January Grace’s funeral was held in Corsham, Wiltshire. A passage by Isaac Penington was read, taken from Quaker Faith and Practice, and Bach’s Concerto for Two Violins in D minor was played. Grace had always loved music. When she was a 19-year-old reporter, she had interviewed a young concert pianist from Manchester, Joan Burns. They remained friends – as lovers of Bach, Chopin, Vaughan Williams – and in 2014 it was Grace who had written Joan’s obituary in the Guardian.

In February there was a memorial event for Grace at her Bedford Quaker Meeting-House. It was mainly her non-stop campaigning for peace that was recalled: handling out leaflets in the centre of Bedford every week against the Iraq War, just as she had done against the Vietnam War – bringing peace closer, shortening the war, saving lives, being vindicated by history. In this connection her son, Chris, read out a tribute to Grace from the former leader of the Labour Party, Jeremy Corbyn. He had worked with Grace in CND, when she was editor of Labour Action for Peace, and about her tireless work he had kind words to say.

Many at the event recalled with a smile her stubborn and uncompromising character but also what fun she could be in her eccentric pertinacity, full of laughter. She was authentic, everyone said; she acted from the heart and at the bidding of her Quaker conscience; she was “hands-on” even at work, walking out of Friends House to collect money for the Kent miners on the picket lines outside Euston Station, and attending to homeless people on the pavement, doing whatever could practically be done…

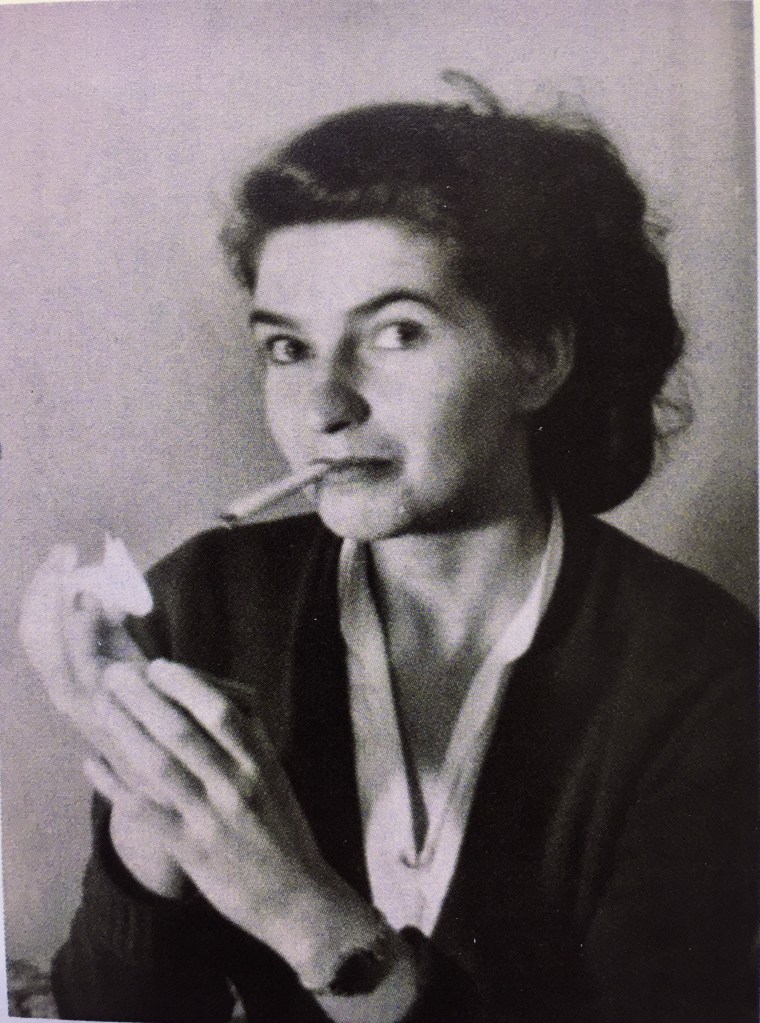

In Memoriam: Grace Crookall-Greening (1928 Nov 13 – 2024 Jan 11).

Leave a reply to Anonymous Cancel reply